Saturday, April 10th, 2021

This week we watched the Venezuelan film Pelo Malo (2014). I think I liked it. It was definitely frustrating and painful and super depressing in the way a lot of queer coming-of-age movies tend to be. As we've discussed in class, it's troubling that there is such a cultural focus on telling stories of queer trauma instead of queer euphoria. At the same time, however, this movie wasn't all trauma. It had a lot of very human and much more realistic writing and characterization.

I want to spend a bit of time connecting this movie to Minari (2021), a Korean-American-made movie about a Korean-American family who moves to Arkansas to start a farm and try to achieve the American dream. As an introduction, there is a trope where movies and stories about people and families of color that make it to the US mainstream always talk about the trauma of racism and play into tropes of drama, which leads white people to expect death, rape, a child's trauma, or something similar as the climax/ending of those movies. Two that come to mind are All the Bright Places (2020), where the black male lead commits suicide at the end, and more recently Concrete Cowboy (2021). While this second one does great work bringing up a specific black riding culture in North Philly, it also has a black male character die almost solely for the purpose of the lead's character development, although at least this time the lead is black. White people then associate people of color with a certain dramatization and theatricality and trauma that isn't realistic or helpful to dismantling white supremacy. I think the same thing happens with queer movies and movies about LGBTQI people. The first example I can think of is how The Imitation Game (2014) ends with Benedict Cumberbatch's character committing suicide. Like yes, it's exposing the horrors of racism and homophobia, but at this point, their existence is old news, and we're never going to get past them if we keep allowing movies to fall into that trope.

This is where Pelo Malo and Minari come in to, in a way, change the conversation. I will start by saying they are both incredibly depressing movies, Pelo Malo especially because it deals with the trauma of a queer child. However, neither of them totally falls into the Hollywood tropes of drama and lack of characterization and a clean-cut Hollywood ending. They both focus instead on the humanization of all their characters of color and the complexities of racism and homophobia.

The family in Minari includes a boy with heart disease and a grandmother, among others, who move to a mostly white town in Arkansas. This sets up the white audience with certain expectations. In a Hollywood movie, either the boy or the grandmother would die by the end, and certainly, there would be a hate crime committed by the white townsfolk against the Korean-American family. Instead, Minari shatters expectations at every turn. The white people in the town talk to the family about almost everything but race. One white person even works on the family's farm. The son's condition improves, and the grandmother's condition deteriorates and she makes mistakes, but she doesn't die. Every member of the family (except the daughter, who could have gotten more attention) gets a chance to share their story and their perspective on screen. None of the issues become clear-cut, there are no protagonists or antagonists, it's just a human family.

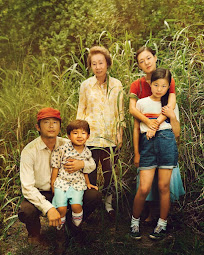

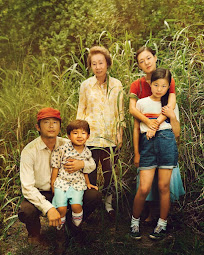

Pela Malo, I would argue, is very similar. I would say this movie focuses a little bit more on trauma and provides fewer opportunities for queer joy and the joy of people of color, but it is progressive in certain important ways. Junior and Marta are both empathetic characters given their own moments, perspectives, and experiences. The son certainly more so, but it's hard not to side with the person with less power in the situation. One way you can see this is in these two stills, the first of which has Junior in focus and the mom out of focus, the second of which has the opposite. There are multiple examples of each of these. When the two characters are together, the mother might behave somewhat cruelly, like when she switches seats on the bus when Junior starts singing, but the camera follows her then, and stays with her, rather than staying with Junior.

We see a similar balance in watching how both of them go through a day. We don't see the mother leave, then stay with the son until the mother returns from whatever she was doing. We follow both of them through their struggles and they each get scenes without the other--the mother walking through the city, waiting at work for the security guard boss, the mother with her lover, the mother sitting alone in her booth singing once she gets her job. The mother is not a full villain in a story about a queer child coming of age, as she might be in an American-made Hollywood movie. She is a human with her own struggles against patriarchy and sexism, and a person with sexual and personal needs. This makes issues of queer families and parenting of queer children more difficult because while we want the son to be loved as a queer child, we can't ignore the humanity, fears, and anxieties of the mother.

Something tangentially related to this humanization of the mother is the idea in the Sedgwick reading about abjection. I am super interested in this. I don't know much about psychology, so I had never heard the term before this class and may not use it totally correctly here. I believe abjection is used in Pelo Malo to turn Junior into a mirror for his mother Marta. Abjection is about seeing your internal excess of self pulled out and presented to you externally, creating a visceral disgust and fear. Marta sees her own rebellion against sexual and gendered norms in Junior, understands the struggles she has had to endure because of them and is disgusted and afraid of seeing those things in Junior. This is interesting to me because, in a queer coming of age movie, the majority of the growth and transformation is now focused on the heteronormative mother instead of the queer child. This forces us to take a step back from issues of queer youth rights and to think about the parents. In a way, it's frustrating and seems stupid that the parent deserves any consideration when we are talking about the life of a child. For the child, being accepted by their parent could be a matter of life or death, so it shouldn't matter what the parent thinks and they should accept them regardless. Maybe part of the film and the article's commentary is that no matter how much we want this to be true, it's impossible to force that onto parents because they are human beings just like their kids.

This blog is becoming incredibly ranting and tangent-y, so let me see if I can just tie things together here. White people and Hollywood have a flair for the dramatic and tend to present and prefer heart-wrenching, often black and white (pun intended?) stories about queer people and people of color where the people in question are mostly victims of abuse and trauma. However, these two films, Minari and Pelo Malo seem revolutionary to me in that they make queer people and people/families of color into actual human beings instead of movie tropes. I'm not sure they push any political agenda other than humanization, but perhaps in the Black Lives Matter era that is a statement that still needs to be made, and will continue to be important until white and cisgender/heterosexual people can acknowledge the humanity of those who are different than them. Amazing that we are still trying to fight for something so basic, but alright.

Thank you for reading and I look forward to y'all's thoughts.

Madeleine Corum

Your analysis of the abject in Pelo Malo is really interesting, I hadn't thought about Marta that way before, that she is sort of seeing her own battles within him and that's why she's trying to get rid of those aspects of him. Also what you said about needing to focus on the parents reminded me of the idea of birthing your parents from the Stockton article, and sort of how kids have to teach their parents by queering their lives and spaces- and I guess how that is really a huge burden placed on queer children.

ReplyDeleteThis analysis encapsulates your discussion point in class about the intersectionality of these stories. There is no pretty or hollywood glam way to speak about BIPOC and queer childhoods, and I am so glad that you highlighted that. I am also intrigued by your analysis of Junior's mother who is [not] a villain but a complex character. You give an opportunity for viewers to see beyond binaries. Your analysis is not generic, and I am happy that I read your blog post.

ReplyDelete